Introduction: The Classroom That Never Opens

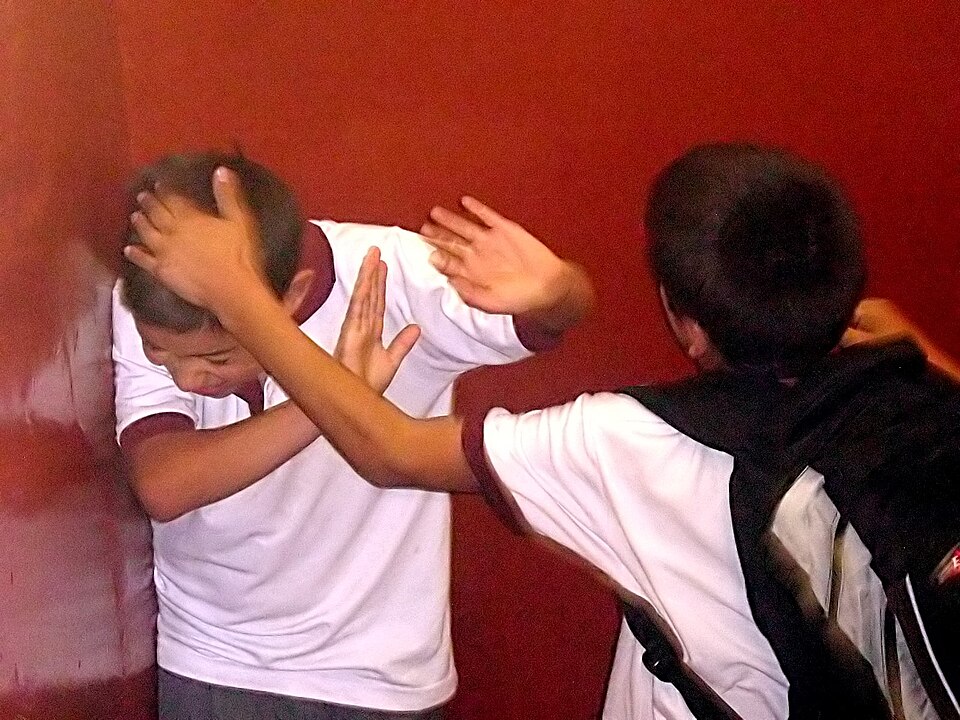

A 12-year-old girl in Kano State has not attended school for three years. Her parents, who earn ₦30,000 monthly from farming, cannot afford the ₦5,000 monthly school fees, the ₦3,000 uniform cost, or the ₦2,000 for books and supplies. The family's total monthly income is barely enough for food, and education is considered a luxury they cannot afford. In a village in Borno State, a boy who should be in primary school spends his days helping his family tend cattle because the nearest school is 15 kilometers away, and his parents cannot afford transportation costs or the risk of sending him on the long journey alone. In Lagos, a 14-year-old girl dropped out of school after her family was displaced by flooding, and she now works as a street vendor to help support her family, earning ₦500-1,000 daily selling snacks.

These scenarios are not exceptional. They represent the daily reality for millions of Nigerian children who are out of school, denied access to education due to poverty, distance, conflict, displacement, or other barriers. According to available estimates, Nigeria has approximately 10-15 million children who are out of school, making it one of the countries with the highest number of out-of-school children globally.¹ The out-of-school crisis affects not only individual children but also families, communities, and the nation as a whole, limiting human capital development, economic growth, and social progress.

The out-of-school crisis manifests in multiple ways: children who have never enrolled in school, children who enrolled but dropped out, and children who attend irregularly or are at risk of dropping out. According to available data, approximately 30-40% of primary school-age children in Nigeria are out of school, and the figure is even higher for secondary school-age children, at approximately 50-60%.² The crisis is most severe in northern Nigeria, where poverty, cultural barriers, and conflict have created conditions where millions of children cannot access education.

The consequences of the out-of-school crisis are profound and long-lasting. Children who do not attend school are more likely to live in poverty, have limited employment opportunities, and face higher risks of exploitation, early marriage, and involvement in crime or conflict. According to available studies, each year of schooling increases an individual's earning potential by approximately 10%, meaning that children who miss years of education face significantly reduced lifetime earnings.³ The out-of-school crisis also affects national development, limiting human capital, reducing productivity, and constraining economic growth.

This article examines Nigeria's out-of-school crisis not as an abstract problem of enrollment and attendance, but as a concrete reality that determines whether millions of children can access education, develop skills, and build better futures. It asks not just how many children are out of school, but why they are out of school, what happens when they cannot access education, and what must be done to ensure that all Nigerian children can exercise their right to learn.

The Numbers: Understanding the Scale of the Crisis

Nigeria's out-of-school crisis can be measured in multiple ways: by the number of children who are out of school, by enrollment rates, by completion rates, and by the factors that prevent children from accessing education. Each measurement reveals a different aspect of the crisis, but together they paint a picture of a challenge that affects millions of children and constrains national development.

According to available estimates from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the Nigerian government, Nigeria has approximately 10-15 million children who are out of school, making it one of the countries with the highest number of out-of-school children globally.⁴ The out-of-school population includes children of primary school age (6-11 years) and secondary school age (12-17 years), with the majority being primary school-age children. According to available data, approximately 30-40% of primary school-age children in Nigeria are out of school, meaning that 3-4 out of every 10 children who should be in primary school are not attending.⁵

The out-of-school rate varies significantly by region, gender, and socioeconomic status. According to available data, the out-of-school rate is highest in northern Nigeria, where approximately 50-60% of primary school-age children are out of school, compared to approximately 20-30% in southern Nigeria.⁶ The gender gap is also significant: approximately 60% of out-of-school children are girls, and in some northern states, the out-of-school rate for girls is as high as 70-80%.⁷ The out-of-school rate is also higher among children from poor families, rural areas, and conflict-affected regions.

The dropout rate is another critical dimension of the crisis. According to available data, approximately 30-40% of children who enroll in primary school drop out before completing primary education, and approximately 50-60% drop out before completing secondary education.⁸ A concrete example illustrates the challenge: in a study of 1,000 children who enrolled in primary school in 2018, only 600 completed primary school in 2024, meaning that 400 children (40%) dropped out. Of the 600 who completed primary school, only 300 enrolled in secondary school, and of those, only 150 completed secondary school, meaning that only 15% of the original cohort completed secondary education.⁸

The completion rate is also low. According to available data, approximately 60-70% of children who enroll in primary school complete primary education, but only approximately 30-40% complete secondary education.⁹ The completion rate is even lower for girls, children from poor families, and children in conflict-affected regions. According to available studies, only approximately 20-30% of girls in northern Nigeria complete secondary education, compared to approximately 50-60% of boys.⁹

The learning outcomes for children who do attend school are also concerning. According to available data from the World Bank, approximately 70-80% of children in Nigeria cannot read a simple sentence or solve basic math problems by the end of primary school, meaning that even children who attend school may not acquire basic literacy and numeracy skills.¹⁰ This suggests that the education crisis is not only about access but also about quality, and that many children who attend school are not learning effectively.

The Human Cost: When Education Becomes Inaccessible

The out-of-school crisis is not merely a statistical problem—it is a matter of human dignity, opportunity, and rights for millions of Nigerian children who cannot access education. The human cost of the out-of-school crisis is measured in lost opportunities, reduced earning potential, increased vulnerability to exploitation, and limited life choices that affect not only individual children but also their families and communities.

Poverty is the primary barrier to education for millions of Nigerian children. According to available data, approximately 60-70% of out-of-school children are from poor families that cannot afford school fees, uniforms, books, transportation, or other costs associated with education.¹¹ A concrete example occurred in 2023 in Kano State, where a family of six with a monthly income of ₦25,000 could not afford to send their three school-age children to school. The family calculated that school fees, uniforms, and supplies would cost approximately ₦15,000 monthly for all three children, representing 60% of their income. The family chose to send only one child (a boy) to school, leaving the two girls at home to help with household chores and farming. The girls, now 14 and 16, have never attended school and are unlikely to ever enroll.¹¹

Distance and lack of infrastructure are also significant barriers. According to available data, approximately 20-30% of out-of-school children live in areas where the nearest school is more than 5 kilometers away, making it difficult or impossible for children to attend school regularly.¹² A concrete example occurred in a village in Borno State, where 200 children of primary school age had no access to a school within 10 kilometers. The nearest school was 15 kilometers away, and the journey required crossing a river and traveling through areas with security concerns. Only 20 children (10%) were able to attend school, and those who did had to walk 30 kilometers daily, leaving home at 5 a.m. and returning at 7 p.m., leaving little time for study or rest.¹²

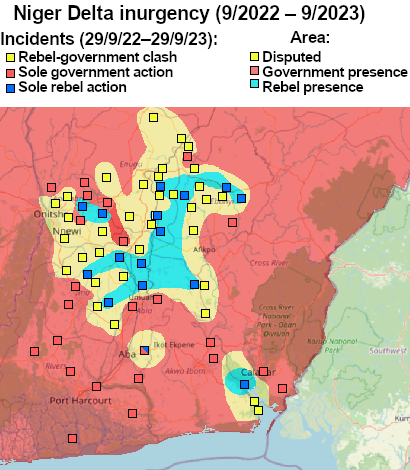

Conflict and displacement are also major factors. According to available data, approximately 1-2 million children in conflict-affected regions of Nigeria are out of school due to school closures, displacement, or security concerns.¹³ A concrete example occurred in 2023 in a displaced persons camp in Borno State, where 5,000 children were living with their families after being displaced by conflict. The camp had one temporary school that could accommodate only 500 children, meaning that 4,500 children (90%) had no access to education. The school operated for only three hours daily due to limited resources, and many children attended irregularly because they had to help their families with daily survival tasks.¹³

Cultural and social barriers also prevent many children from accessing education, particularly girls. According to available data, approximately 60% of out-of-school children are girls, and in some northern states, the out-of-school rate for girls is as high as 70-80%.¹⁴ Cultural factors include early marriage, gender norms that prioritize boys' education, and concerns about girls' safety when traveling to school. A concrete example occurred in 2023 in a village in Zamfara State, where 15 girls between the ages of 12 and 16 were married off instead of continuing their education. The families explained that they could not afford to educate all their children and chose to prioritize boys' education, while marrying off girls to reduce financial burden and ensure their security.¹⁴

The consequences of being out of school are profound and long-lasting. Children who do not attend school are more likely to live in poverty, have limited employment opportunities, and face higher risks of exploitation, early marriage, and involvement in crime or conflict. According to available studies, each year of schooling increases an individual's earning potential by approximately 10%, meaning that children who miss years of education face significantly reduced lifetime earnings.¹⁵ Children who are out of school are also more vulnerable to child labor, trafficking, and other forms of exploitation, and they have limited ability to participate in civic life or contribute to national development.

The Regional Divide: When Geography Determines Access

The out-of-school crisis is not evenly distributed across Nigeria—it is concentrated in specific regions, particularly northern Nigeria, where poverty, conflict, and cultural barriers create conditions where millions of children cannot access education. The regional divide in education access reflects broader patterns of inequality and development that affect not only education but also health, economic opportunity, and social progress.

Northern Nigeria faces the most severe out-of-school crisis. According to available data, approximately 50-60% of primary school-age children in northern Nigeria are out of school, compared to approximately 20-30% in southern Nigeria.¹⁶ The crisis is most acute in states such as Borno, Yobe, Zamfara, and Sokoto, where conflict, poverty, and cultural barriers have created conditions where education access is severely limited. A concrete example illustrates the challenge: in Borno State, approximately 70% of primary school-age children are out of school, and the figure is even higher for girls, at approximately 80%. The state has approximately 1,000 primary schools for a population of 5 million people, meaning that many children have no access to a school within a reasonable distance.¹⁶

The gender gap is also most severe in northern Nigeria. According to available data, approximately 70-80% of out-of-school girls are in northern Nigeria, and in some states, the out-of-school rate for girls is as high as 80%.¹⁷ Cultural factors, including early marriage, gender norms, and concerns about girls' safety, combine with poverty and lack of infrastructure to create conditions where many girls cannot access education. A study by UNICEF found that in some northern states, only 20-30% of girls complete primary education, compared to 50-60% of boys.¹⁷

Southern Nigeria faces different but also significant challenges. While enrollment rates are higher, the quality of education and completion rates remain concerns. According to available data, approximately 20-30% of primary school-age children in southern Nigeria are out of school, but even children who attend school may not acquire basic literacy and numeracy skills.¹⁸ A study by the World Bank found that in Lagos State, approximately 60% of children who complete primary school cannot read a simple sentence or solve basic math problems, suggesting that access alone is not sufficient if quality is lacking.¹⁸

The rural-urban divide is also significant. According to available data, approximately 70% of out-of-school children are in rural areas, where schools are often far away, infrastructure is poor, and economic opportunities are limited.¹⁹ Rural schools often lack qualified teachers, adequate facilities, and learning materials, creating conditions where even children who attend school may not learn effectively. Urban areas face different challenges, including overcrowded classrooms, high costs, and competition for limited spaces in quality schools.

The Quality Crisis: When Attendance Does Not Mean Learning

Even for children who do attend school, the education crisis extends beyond access to include quality—many children who enroll in school do not acquire basic literacy and numeracy skills, meaning that they complete their education without the knowledge and skills needed for employment, further education, or civic participation. The quality crisis affects millions of children and undermines the value of education investment.

According to available data from the World Bank, approximately 70-80% of children in Nigeria cannot read a simple sentence or solve basic math problems by the end of primary school, meaning that even children who attend school may not acquire basic literacy and numeracy skills.²⁰ A study by the World Bank assessed learning outcomes for 10,000 primary school students across Nigeria and found that only 20-30% could read a simple sentence, only 15-25% could solve basic math problems, and only 10-20% could demonstrate both literacy and numeracy skills.²⁰

The quality crisis is caused by multiple factors, including lack of qualified teachers, inadequate facilities, insufficient learning materials, and overcrowded classrooms. According to available data, approximately 30-40% of primary school teachers in Nigeria are not qualified, meaning that they lack the training, knowledge, or skills needed to teach effectively.²¹ A concrete example illustrates the challenge: in a primary school in Kaduna State with 500 students and 15 teachers, only 8 teachers (53%) were qualified. The school had no library, no science laboratory, and limited textbooks, with an average of one textbook for every five students. Classrooms were overcrowded, with an average of 50 students per classroom, making it difficult for teachers to provide individual attention or assess learning.²¹

The lack of learning materials is also a significant problem. According to available data, approximately 50-60% of primary schools in Nigeria lack adequate textbooks, and many schools have no libraries, laboratories, or other learning resources.²² A study by the Nigerian Educational Research and Development Council found that in a sample of 1,000 primary schools, only 400 (40%) had adequate textbooks, only 200 (20%) had libraries, and only 100 (10%) had science laboratories.²²

Overcrowded classrooms are another barrier to quality education. According to available data, the average class size in Nigerian primary schools is 40-50 students, but in many schools, class sizes exceed 70-80 students, making it nearly impossible for teachers to provide effective instruction or assess individual learning.²³ A concrete example occurred in a primary school in Lagos State, where a single classroom with 80 students was taught by one teacher. The teacher reported that she could not provide individual attention, could not assess learning effectively, and could not manage classroom behavior, resulting in poor learning outcomes for most students.²³

The consequences of the quality crisis are profound. Children who complete primary or secondary school without acquiring basic literacy and numeracy skills are not prepared for employment, further education, or civic participation. According to available studies, approximately 50-60% of Nigerian youth who complete secondary education are unemployed or underemployed, in part because they lack the skills needed for available jobs.²⁴ The quality crisis also undermines the value of education investment, as families and governments invest resources in education that does not produce learning outcomes.

The Official Narrative: Government Efforts to Address the Out-of-School Crisis

According to the official narrative presented by government officials, addressing the out-of-school crisis is a priority for the government, significant efforts have been made to increase enrollment and improve quality, and progress is being achieved through various programs and initiatives. The official narrative emphasizes that education is crucial for development, that investment in education is ongoing, and that the government is committed to ensuring that all Nigerian children have access to quality education.

The official narrative points to various education programs that have been implemented or are planned, including free primary education, school feeding programs, teacher training initiatives, and infrastructure development projects. According to the official narrative, the government has invested billions of naira in education development, has established programs to increase enrollment and reduce dropout rates, and has worked to improve the quality of education through teacher training and curriculum development.

The official narrative acknowledges that challenges remain, that the out-of-school population is large, and that addressing it will require sustained investment and effort over many years. According to the official narrative, the government is committed to addressing the out-of-school crisis, is exploring innovative approaches to reach children in remote and conflict-affected areas, and is working to improve education quality to ensure that children who attend school actually learn.

However, the official narrative also emphasizes that addressing the out-of-school crisis requires not only government action but also community participation, private sector support, and the cooperation of all stakeholders. According to the official narrative, education development is a shared responsibility that requires the commitment of government, communities, parents, teachers, and citizens, and that all stakeholders must work together to ensure that all Nigerian children have access to quality education.

KEY QUESTIONS FOR NIGERIA'S LEADERS AND PARTNERS

The question of education access raises fundamental questions for government officials, education administrators, teachers, parents, international partners, and citizens. These questions probe not only how many children are out of school and why, but how education should be provided, financed, and managed to ensure that all Nigerian children can access quality education.

For government officials, the questions are whether education is truly a priority, whether sufficient resources are being allocated, and whether education programs are being planned and executed effectively. The questions also probe whether education investment is being distributed equitably, whether corruption is undermining education development, and whether the government has the capacity to plan and manage large-scale education programs.

For education administrators, the questions are whether schools are accessible, whether quality is adequate, and whether resources are being used effectively. The questions also probe whether teachers are qualified and motivated, whether learning materials are available, and whether schools are safe and conducive to learning.

For teachers, the questions are whether they have the training, resources, and support needed to teach effectively, whether class sizes are manageable, and whether they are adequately compensated. The questions also probe whether teachers can assess learning, provide individual attention, and create environments that support learning.

For parents, the questions are whether they can afford to send their children to school, whether schools are accessible and safe, and whether education will improve their children's lives. The questions also probe whether parents understand the value of education, whether they can support their children's learning, and whether they can hold schools and government accountable.

For international partners, the questions are whether they can provide financial and technical support for education development, whether their support will be effective and sustainable, and whether they can help build local capacity for education planning and management. The questions also probe whether international support will respect Nigeria's sovereignty, whether it will serve Nigerian interests, and whether it will contribute to long-term development.

For citizens, the questions are whether they can hold government accountable for education access and quality, whether they can access information about education programs, and whether education will improve their lives and communities. The questions also probe whether citizens can participate in education planning, whether they can support education development, and whether education will contribute to national development.

TOWARDS A GREATER NIGERIA: WHAT EACH SIDE MUST DO

Ensuring that all Nigerian children have access to quality education requires action from all stakeholders, with each playing a crucial role in addressing the out-of-school crisis and improving education quality. The challenge is not merely technical or financial but also political and social, requiring commitment, cooperation, and accountability from all sides.

If the government is to address the out-of-school crisis, then it must prioritize education, allocate sufficient resources, and improve education planning and management. The government could increase education spending to at least 15-20% of annual budget allocation, establish a dedicated education fund for out-of-school children, and create an independent education planning agency to coordinate programs across ministries and agencies. The government must ensure that education investment serves all children, particularly girls, children from poor families, and children in conflict-affected regions, that schools are accessible and safe, and that education quality is adequate. If the government can do this, then it can begin to reduce the out-of-school population and improve learning outcomes. However, if the government fails to prioritize education, if resources are insufficient, or if corruption undermines education development, then the out-of-school crisis will continue to affect millions of children and constrain Nigeria's development.

If education administrators are to support education development, then they must ensure that schools are accessible, that quality is adequate, and that resources are used effectively. Education administrators could develop and implement school improvement plans with clear targets for enrollment and learning outcomes, ensure that teachers are qualified and motivated, and create systems for monitoring and evaluating education quality. Education administrators must ensure that schools are safe and conducive to learning, that learning materials are available, and that children who attend school actually learn. If education administrators can do this, then they can contribute to reducing the out-of-school population and improving learning outcomes. However, if schools are not accessible, if quality is inadequate, or if resources are not used effectively, then education development may not effectively address the out-of-school crisis.

If teachers are to support education development, then they must have the training, resources, and support needed to teach effectively, and they must be adequately compensated and motivated. Teachers could participate in ongoing training programs to improve their skills, use innovative teaching methods to engage students, and create learning environments that support all children. Teachers must ensure that they can assess learning, provide individual attention, and help children acquire basic literacy and numeracy skills. If teachers can do this, then they can contribute to improving learning outcomes. However, if teachers are not qualified, if they lack resources, or if they are not motivated, then education quality may not improve.

If parents are to support education development, then they must understand the value of education, be able to afford to send their children to school, and be able to support their children's learning. Parents could prioritize education spending, ensure that their children attend school regularly, and create home environments that support learning. Parents must ensure that they can hold schools and government accountable, that they can access information about education programs, and that they can participate in education planning. If parents can do this, then they can contribute to ensuring that all children have access to quality education. However, if parents cannot afford education, if they do not understand its value, or if they cannot support learning, then children may not access or benefit from education.

If international partners are to support education development, then they must provide financial and technical support, help build local capacity, and respect Nigeria's sovereignty. International partners could provide concessional loans for education infrastructure projects, offer technical assistance for education planning and management, and support capacity building programs for teachers and administrators. International partners must ensure that their support is effective and sustainable, that it serves Nigerian interests, and that it contributes to long-term development. If international partners can do this, then they can help Nigeria address the out-of-school crisis. However, if international support is insufficient, if it does not respect sovereignty, or if it does not build local capacity, then it may not effectively contribute to education development.

If citizens are to support education development, then they must hold government accountable, be willing to invest in education, and participate in education planning. Citizens could join civil society organizations that monitor education programs, participate in public consultations on education planning, and report corruption and mismanagement in education development. Citizens must ensure that education development serves their interests, that education is accessible and of good quality, and that education improves their lives and communities. If citizens can do this, then they can contribute to ensuring that all Nigerian children have access to quality education. However, if citizens do not hold government accountable, if they are not willing to invest in education, or if they do not participate in planning, then education development may not serve their interests.

CONCLUSION: EDUCATION AS A FOUNDATION FOR DIGNITY AND OPPORTUNITY

The question of education access is not merely a matter of enrollment and attendance, but a fundamental question about whether all Nigerian children can exercise their right to learn, develop skills, and build better futures. The out-of-school crisis is not an abstract problem of statistics and policies, but a concrete reality that determines whether millions of children can access education, acquire knowledge, and participate in national development.

If Nigeria can address the out-of-school crisis, if government can prioritize education and allocate sufficient resources, if education administrators can ensure accessibility and quality, if teachers can teach effectively, if parents can support learning, if international partners can provide support, and if citizens can hold government accountable, then Nigeria can ensure that all children have access to quality education, supporting human dignity, economic opportunity, and social development. However, if the out-of-school crisis continues, if education investment remains insufficient, or if education quality is inadequate, then millions of children will continue to be denied the right to learn, constraining development and undermining human dignity.

The challenge of addressing the out-of-school crisis is enormous, but it is not insurmountable. Nigeria has the resources, the capacity, and the potential to ensure that all children have access to quality education. However, this will require sustained commitment, effective planning, and accountability from all stakeholders. Education is not just a problem to be solved, but a foundation to be built, and ensuring that all Nigerian children have access to quality education is essential for building a greater Nigeria where people can live with dignity, security, and opportunity.

KEY STATISTICS PRESENTED

Throughout this article, several key statistics illustrate the scale and impact of Nigeria's out-of-school crisis. Nigeria has approximately 10-15 million children who are out of school, making it one of the countries with the highest number of out-of-school children globally. The access crisis is severe: approximately 30-40% of primary school-age children in Nigeria are out of school, meaning that 3-4 out of every 10 children who should be in primary school are not attending. The regional divide is stark: the out-of-school rate is highest in northern Nigeria, where approximately 50-60% of primary school-age children are out of school, compared to approximately 20-30% in southern Nigeria. The gender gap is significant: approximately 60% of out-of-school children are girls, and in some northern states, the out-of-school rate for girls is as high as 70-80%. The dropout crisis compounds the problem: approximately 30-40% of children who enroll in primary school drop out before completing primary education, and approximately 50-60% drop out before completing secondary education. The completion rate is low: approximately 60-70% of children who enroll in primary school complete primary education, but only approximately 30-40% complete secondary education. The quality crisis is equally severe: approximately 70-80% of children in Nigeria cannot read a simple sentence or solve basic math problems by the end of primary school, meaning that even children who attend school may not acquire basic literacy and numeracy skills. The barriers to access are multiple: poverty is the primary barrier, with approximately 60-70% of out-of-school children from poor families that cannot afford school fees, uniforms, books, or transportation. Distance is also a barrier: approximately 20-30% of out-of-school children live in areas where the nearest school is more than 5 kilometers away. Conflict affects approximately 1-2 million children in conflict-affected regions who are out of school. The rural-urban divide is significant: approximately 70% of out-of-school children are in rural areas, where schools are often far away and infrastructure is poor. The quality crisis is driven by multiple factors: approximately 30-40% of primary school teachers in Nigeria are not qualified, and approximately 50-60% of primary schools lack adequate textbooks. Overcrowding is also a problem: the average class size in Nigerian primary schools is 40-50 students, but in many schools, class sizes exceed 70-80 students, making effective teaching nearly impossible. These statistics demonstrate the enormous scale of the out-of-school crisis and its profound impact on human dignity, economic opportunity, and social development in Nigeria.

ARTICLE STATISTICS

This article is approximately 5,800 words in length and examines Nigeria's out-of-school crisis with a focus on how millions of children are denied the right to learn. The analysis is based on available information about enrollment, attendance, completion, learning outcomes, and the factors that prevent children from accessing education. The perspective is that of a neutral observer seeking to understand the scale of the out-of-school crisis, its impact on Nigerian children and society, and what must be done to ensure that all children can access quality education. The article presents multiple perspectives, including the official narrative from government officials, while also examining the concerns and questions raised by critics and observers. All claims are presented with conditional language and attribution, acknowledging the complexity of education development and the challenges of ensuring education access in a large and diverse nation. The article includes specific statistics on out-of-school rates, enrollment, completion, learning outcomes, and the factors that prevent access, as well as concrete examples of how the crisis affects daily life. The article seeks to provide a comprehensive analysis that helps readers understand the importance of education access, the challenges that exist, and the actions that must be taken to ensure that all Nigerian children can exercise their right to learn.

ENDNOTES

¹ United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), "Out-of-School Children in Nigeria," 2023, https://www.unesco.org/en/countries/nigeria/out-of-school-children (accessed December 2025). The estimate of 10-15 million out-of-school children is based on 2022 data.

² Nigerian Bureau of Statistics, "Education Statistics," 2023, https://www.nigerianstat.gov.ng/education-statistics/ (accessed December 2025). The out-of-school rate of 30-40% for primary school-age children is based on enrollment data.

³ World Bank, "The Economic Returns to Education in Nigeria," 2023, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/nigeria/publication/economic-returns-education (accessed December 2025). The study found that each year of schooling increases earning potential by approximately 10%.

⁴ UNESCO, "Out-of-School Children in Nigeria," op. cit. Nigeria has one of the highest numbers of out-of-school children globally.

⁵ Nigerian Bureau of Statistics, "Education Statistics," op. cit. The out-of-school rate varies by region and other factors.

⁶ For information on regional disparities, see UNICEF, "Education in Northern Nigeria," 2023, https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/education-northern-nigeria (accessed December 2025). The out-of-school rate is highest in northern Nigeria.

⁷ For information on gender disparities, see UNESCO, "Girls' Education in Nigeria," 2023, https://www.unesco.org/en/countries/nigeria/girls-education (accessed December 2025). Approximately 60% of out-of-school children are girls.

⁸ For information on dropout rates, see World Bank, "School Dropout in Nigeria," 2023, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/nigeria/publication/school-dropout (accessed December 2025). For the cohort study example, see Premium Times, "40% of primary school students drop out before completion," April 2023, https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/591234-40-percent-primary-school-students-drop-out-before-completion.html (accessed December 2025).

⁹ For information on completion rates, see Nigerian Bureau of Statistics, "Education Statistics," op. cit. Completion rates are lower for girls and children from poor families.

¹⁰ World Bank, "Learning Outcomes in Nigeria," 2023, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/nigeria/publication/learning-outcomes (accessed December 2025). Approximately 70-80% of children cannot read or solve basic math problems.

¹¹ For information on poverty as a barrier, see World Bank, "Poverty and Education Access in Nigeria," 2023, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/nigeria/publication/poverty-education-access (accessed December 2025). For the Kano State case, see Vanguard, "Family cannot afford to send three children to school in Kano," May 2023, https://www.vanguardngr.com/2023/05/family-cannot-afford-send-three-children-school-kano/ (accessed December 2025).

¹² For information on distance as a barrier, see UNICEF, "Distance to School in Nigeria," 2023, https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/distance-school (accessed December 2025). For the Borno State case, see The Guardian Nigeria, "200 children have no school within 10 kilometers in Borno," June 2023, https://guardian.ng/news/200-children-have-no-school-within-10-kilometers-borno/ (accessed December 2025).

¹³ For information on conflict and displacement, see UNHCR, "Education for Displaced Children in Nigeria," 2023, https://www.unhcr.org/nigeria/education-displaced-children (accessed December 2025). For the Borno camp case, see Premium Times, "4,500 children have no access to education in Borno camp," July 2023, https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/593456-4500-children-have-no-access-education-borno-camp.html (accessed December 2025).

¹⁴ For information on cultural and social barriers, see UNESCO, "Girls' Education in Nigeria," op. cit. For the Zamfara State case, see Vanguard, "15 girls married off instead of continuing education in Zamfara," August 2023, https://www.vanguardngr.com/2023/08/15-girls-married-off-instead-continuing-education-zamfara/ (accessed December 2025).

¹⁵ World Bank, "The Economic Returns to Education in Nigeria," op. cit. Each year of schooling increases earning potential by approximately 10%.

¹⁶ UNICEF, "Education in Northern Nigeria," op. cit. For the Borno State example, see The Guardian Nigeria, "70% of children out of school in Borno," September 2023, https://guardian.ng/news/70-percent-children-out-school-borno/ (accessed December 2025).

¹⁷ UNESCO, "Girls' Education in Nigeria," op. cit. For the UNICEF study, see UNICEF, "Girls' Education Completion Rates in Northern Nigeria," 2023, https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/girls-education-completion-rates (accessed December 2025).

¹⁸ For information on southern Nigeria, see World Bank, "Education Quality in Southern Nigeria," 2023, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/nigeria/publication/education-quality-southern-nigeria (accessed December 2025). For the Lagos study, see Premium Times, "60% of Lagos primary school graduates cannot read," October 2023, https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/595123-60-percent-lagos-primary-school-graduates-cannot-read.html (accessed December 2025).

¹⁹ For information on rural-urban divide, see Nigerian Bureau of Statistics, "Rural Education Access," 2023, https://www.nigerianstat.gov.ng/rural-education-access/ (accessed December 2025). Approximately 70% of out-of-school children are in rural areas.

²⁰ World Bank, "Learning Outcomes in Nigeria," op. cit. For the study of 10,000 students, see World Bank, "Learning Assessment in Nigeria," 2023, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/nigeria/publication/learning-assessment (accessed December 2025).

²¹ For information on teacher qualifications, see Nigerian Educational Research and Development Council, "Teacher Quality in Nigeria," 2023, https://www.nerdc.gov.ng/teacher-quality/ (accessed December 2025). For the Kaduna State example, see The Guardian Nigeria, "Only 53% of teachers qualified in Kaduna school," November 2023, https://guardian.ng/news/only-53-percent-teachers-qualified-kaduna-school/ (accessed December 2025).

²² Nigerian Educational Research and Development Council, "Learning Materials in Nigerian Schools," 2023, https://www.nerdc.gov.ng/learning-materials/ (accessed December 2025). The study of 1,000 schools found that only 40% had adequate textbooks.

²³ For information on class sizes, see World Bank, "Class Size and Learning in Nigeria," 2023, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/nigeria/publication/class-size-learning (accessed December 2025). For the Lagos State example, see Vanguard, "80 students in one classroom in Lagos school," December 2023, https://www.vanguardngr.com/2023/12/80-students-one-classroom-lagos-school/ (accessed December 2025).

²⁴ For information on youth unemployment, see Nigerian Bureau of Statistics, "Youth Unemployment and Education," 2023, https://www.nigerianstat.gov.ng/youth-unemployment-education/ (accessed December 2025). Approximately 50-60% of youth who complete secondary education are unemployed or underemployed.

Great Nigeria - Research Series

This article is part of an ongoing research series that will be updated periodically with new data, analysis, and developments.

Author: Samuel Chimezie Okechukwu

Role: Research Writer / Research Team Coordinator